They were not always the polite occasions they are now

Rioting, disorder and alcohol-fuelled mob violence were once so commonplace in British elections that an Act of Parliament had to be passed to clean things up.

These days a hustings is a meeting of candidates ahead of an election, a largely civilised and polite occasion in which people of all political persuasions sit down at the same table.

They pass microphones around and take turns to answer questions, allowing their opponents uninterrupted time to speak before putting their own views.

When the chairman or chairwoman of the session tells them their time is up, they demur politely and hand over the mic.

It was not always like that.

The word ‘hustings’ derives from old English and Norse expressions for an assembly of the followers or household retainers of a king, an earl or a chief. Literally, it means ‘house things’.

By the early eighteenth century it had come to mean much the same as it does now, a platform for political speeches, but in the days before literacy was widespread, it was a way of nominating candidates and even electing members to the House of Commons.

After each candidate had spoken, a show of hands was taken to indicate the opinion of the voters. Following the Reform Act of 1832, a hustings was required for every 600 electors, which at that time, of course, did not include women.

Only around seven per cent of the population could actually vote in 1832, although everyone was free to have their say at the hustings.

By the late nineteenth century, however, hustings were getting out of hand.

Radical reformer John Bright, a Lancastrian who had fought against the punitive corn laws, advocated the modern-style secret ballot as a replacement for hustings events which, he said, were marred by ‘tumult and disorder’.

Alcohol had turned audiences into violent mobs.

In Chepstow in 1847 the arrival of a wagon laden with barrels of beer was the trigger for extreme violence at a hustings event organised by Captain Henry Somerset.

One man died after falling out of the beer wagon and fracturing his skull and several others were severely injured. The home of the local vicar was vandalised and Captain Somerset himself was set upon by members of the drunken mob, described in a local newspaper as ‘the lower orders’.

The Ballot Act 1872 introduced the much-prized secret vote, and stopped the hustings being the method by which candidates were nominated. The current system of submitting signed nomination papers to establish candidates came in at the same time.

Attending a hustings event is somewhat safer these days, but do listen out for the arrival of the beer wagon just in case.

Hustings continue around the county. Among those in the coming days, the Exeter Youth Hustings is at St Davids Church at 1215, Hele Road, Exeter, organised by Exeter College students. On Friday, a Devon business organised by Devon and Plymouth Chamber is at the Devonport Lecture Theatre, University of Plymouth, at 11am moderated by Paul Nero, editor of LDRS Devon. Places can be booked by calling 01752 273880.

Rocket builder careers in Cornwall to soar

Rocket builder careers in Cornwall to soar

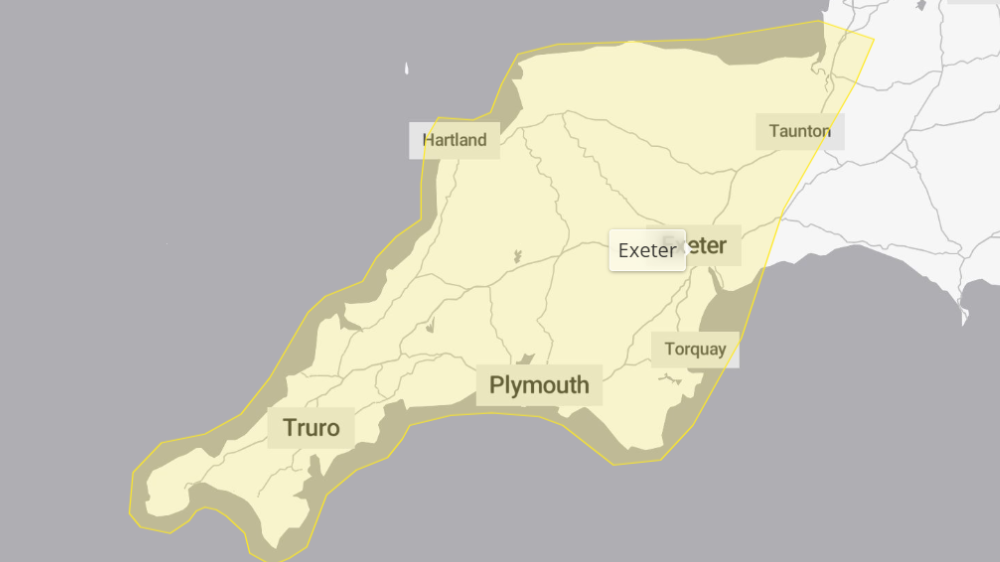

'Twas the weather warning before Christmas

'Twas the weather warning before Christmas

Police watchdog investigates after fatal Plymouth crash

Police watchdog investigates after fatal Plymouth crash

Torbay memorial bench prices top London's

Torbay memorial bench prices top London's

There’s No Place Like an Exeter Panto

There’s No Place Like an Exeter Panto